What the Heck Is Going on in New York? MMA’s Legal Gray-Area in the Empire State

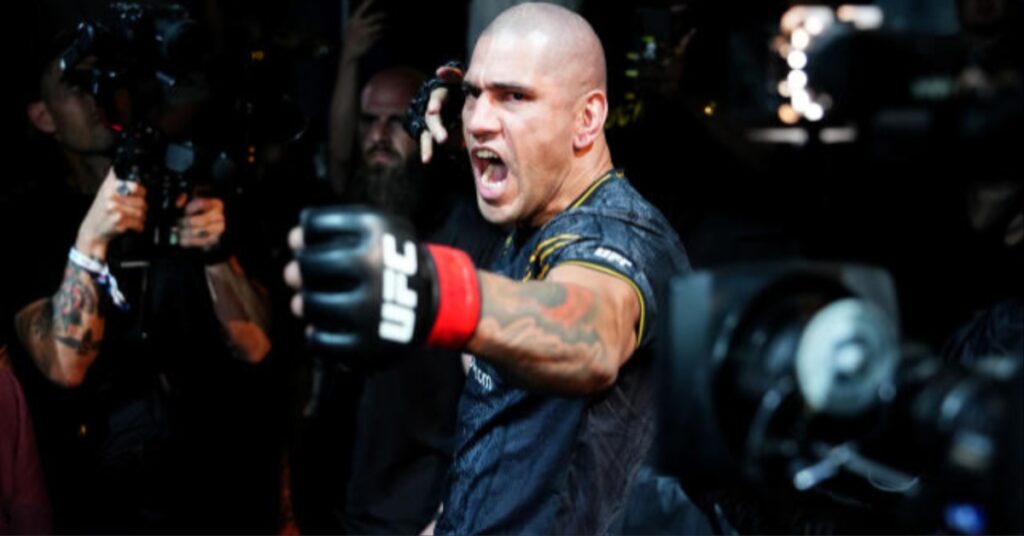

(A nice little Sunday at the Underground Combat League. / All photos courtesy of the author.)

By Jim Genia

The UFC held a show in Buffalo, N.Y., in 1995, and all was well and good. That is, until New York banned professional mixed martial arts in 1997 on the grounds that it was “human cockfighting” and fights to the death suck. Or something like that. But the passage of time has seen the sport evolve, and now MMA is sanctioned almost everywhere in the country — everywhere but New York.

So last year Zuffa filed a lawsuit against the state alleging that the ban violated all sorts of Constitutional rights, and while the suit is currently mired in the muck of the judicial process, and efforts to change the law via the legislature get bogged down year after maddening year, something has changed. Depending on where you live in the state, it’s now possible to take in an MMA event live. There are shows sprouting up on the sovereign territory of Indian Reservations, and amateur MMA competitions are kicking off in ice skating rinks and in armories — all of them happening pretty much unmolested by an athletic commission that went from “search and destroy” mode to laissez-faire in seemingly the blink of an eye. Which begs the question: What the heck is going on in New York?

The short answer is that there’s a lot going in New York. The long answer, however, involves an athletic commission finally admitting that amateur MMA is legal, fights on Indian Land, and an underground fight scene that shows no signs of slowing down.

The Word from Above

When Governor George Pataki and the State Legislature enacted the law that banned pro MMA, their ire was aimed squarely at the sport’s two biggest offenders — the UFC and Extreme Fighting (the UFC’s top competitor), both of whom were planning events in the Empire State at the time. But while the 1997 ban was effective in keeping those promotions out (and it even spelled doom for Extreme Fighting), no one in charge really cared about the MMA bouts that popped up here and there on kickboxing cards. Athletic commission officials even sat ringside as guests, watching newcomers like Matt Serra and Phil Baroni do their thing at events that took place in nightclubs on Long Island and hotel ballrooms in Manhattan. As long as the UFC was kept far away, it was all good in the ‘hood.

Things took a turn in 2003, when the athletic commission actively began to shut down anything and everything that involved dudes smashing each other — a move that drove most established promotions out of state, and fostered the growth of New York’s underground fight scene. Why the sudden about-face? Since commissioners are appointed, and they and their staff can come and go like the tide, the 2003 policy shift has always been attributed to the occasional changing of the guard. For the official word, CagePotato reached out to the athletic commission last week.

“The New York State Athletic Commission’s stance with respect to combative sports has remained consistent and has always complied with applicable statutes and regulations,” said NYSAC spokesman Edison Alban via email. “Prior enforcement actions taken by the NYSAC have related to events where prohibited activities, such as unsanctioned boxing and professional martial arts, have been featured.”

Sadly, that answer does nothing to address the amateur combative sporting events that were stamped out.

What of the amateur events that are happening throughout the state now? Thanks to Zuffa’s lawsuit, and the State’s subsequent Motion to Dismiss, it was finally acknowledged by one and all that the law banning pro MMA does nothing to prohibit the amateur version of the sport.

Said Alba: “The New York State Athletic Commission has no regulatory or legal authority over amateur events. The Commission defers to local authorities with respect to whether such events comply with local statutes and ordinances.”

Of course, it helps matters that the current athletic commission regime includes Chairwoman Melvina Lathan, who’s made no secret her appreciation of the sport. Given what the Zuffa case forced the State to admit, and the Commission’s change in posture, it’s no wonder that amateur events have flourished.

(One last question to the Commission, one that Cagepotato couldn’t help but asking: How soon until after the ban is lifted can we start seeing pro shows, like a UFC at Madison Square Garden or a Bellator at the Barclays Center in Brooklyn? “The Commission will not speculate on this,” said Alban.)

Fights on Indian Land

Ryan Ciotoli is sick of traveling. As head coach of the Bombsquad, an MMA team based out of the city of Cortland in Upstate New York, the former collegiate wrestler must trek with his fighters all over the Northeast just so they can compete professionally. To put it bluntly, driving back and forth to places like Maine and South Jersey, over and over again, stinks. But what other option do you have when your state refuses to sanction pro MMA events? For Ciotoli, thinking outside the box involves finding an Indian Reservation (of which New York has a few) willing to host MMA shows, and donning a promoter’s hat. After all, federally-recognized reservations are places where state laws don’t apply. Thus, Gladius Fights was born. Friday, September 22, will be the first event.

“It’s on Sovereign Territory,” said Ciotoli, who is credited with being one of UFC champ Jon Jones’ first coaches in the sport. “It’s going to be in Irving, New York, which is Seneca territory, and the Seneca athletic commission will be overseeing our show. They’ve done shows in the past — they’ve done the Raging Wolf shows, and a couple other smaller shows, so they have some experience. It’s important to us to host a show in New York because there are a lot of pro New York teams and New York fighters and amateur MMA fighters that are aspiring to be professionals. It’s a good home for those guys. Oftentimes we’re travelling to New Jersey, Atlantic City, Massachusetts. We just had a road trip to Maine, which is eight hours, so we’re travelling quite a bit. It’s just nice to have something in your own backyard.”

In terms of running a show, this isn’t Ciotoli’s first time at bat. “We’ve done some amateur shows,” he said. “We started up a league called Fortune Fight League. I think we just got sick of waiting for New York to pass the law to allow [pro] mixed martial arts in the State of New York. So we started looking for venues on that territory, and they just built a brand new facility called the Cattaraugus Sports Arena and it’s pretty modern and perfect for mixed martial arts.” He added: “We’ve done certain aspects of professional shows. I’ve done some matchmaking before…Obviously, we’ve managed a lot of fighters. We’ve just been around mixed martial arts for a long time, and I think we’ve got a pretty good understanding of the sport.”

“Our goal with Gladius Fights is to bring good fights to fans,” said Ciotoli. “Good local fights. You know, guys from New York, and give them the opportunity to fight in front of their fans. Many times, we’re going to other states, and we’re being booed. It’s hard to travel, it’s hard to be the ‘away team’ all the time. It’s just giving fighters a place to compete.”

Clearly, Ciotoli has pros on his team that need fights. But he has amateurs as well. Why not promote more amateur events? “You know, we’ve considered it, but there are so many shows right now that are scheduled — it’s a lot of competition. I know we’d do better than anyone else just because we’ve been involved in the sport the longest in Upstate New York. But it’s touchy, because they’re not using any commissions or sanctioning bodies, and we’ve been to a couple shows already and it’s a mess. It’s dangerous. If you don’t have the proper people in place to run an event, or the proper commission, it’s not good to host those types of events. I would probably stay away from it. Again, the Seneca commission is great. They’ve got a lot of experience, and they oversee the fights. You can’t ask for anything more. I don’t think we’d touch amateur MMA right now.” He added: “I kind of disagree with a lot of those amateur MMA shows. I mean, we’ve competed in a couple of them, and you’d be shocked. It looks like it did ten, fifteen years ago. It’s the Wild West up here.”

The Underground Scene

It’s the Wild West in New York City, too.

It’s Sunday afternoon at a secret location in the South Bronx, and Peter Storm — the man behind the Underground Combat League (UCL) — is running around with a Post-It scrawled with names. It’s the fight card, and as usual it’s an amorphous thing, so in gi pants and four-ounce MMA gloves (Storm’s is one of the names on the Post-It), he’s doing his best to make sure everyone who wants to fight gets one.

February will mark the ten-year anniversary of the UCL, and with over forty installments — held in always-changing locations within the Five Boroughs — it would be hard to label the illicit fighting organization as “just a bunch of dudes throwing down.” In fact, mixed in with the wannabes, thugs, and psychos who’ve stepped into the UCL ring, there have been quite a few legitimate MMA fighters, including licensed amateurs and pros from out of state. Former UFC champ Frankie Edgar even fought there, back in 2005.

Like Ciotoli, Storm chose not to wait for New York to start sanctioning the sport. Unlike Ciotoli, though, Storm saw the amateur loophole as an opportunity. How does he feel about the State now admitting that amateur shows are okay and the sudden explosion of promotions?

“Not too good, because at the end of the day there’s really no appreciation,” he said. “Everybody’s acting like they found the stipulation in the law themselves, and they’re not acknowledging what I’ve done.”

The fights begin. An ardent kung fu practitioner falls prey to a guillotine choke and taps out in about twenty seconds. He wants more, and gets back in there to face a Jeet Kune Do stylist from Harlem; this time he taps out to an armbar about two minutes in — an improvement, at least. Meanwhile, Storm fights a Muslim kickboxer, and after taking him down and delivering a series of headbutts (UCL fights are often vale tudo), he taps his foe with a kimura. The main event sees a Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu purple belt named Chad go back and forth with a submission wrestler named Pedro. Pedro opens up a cut under Chad’s eye with a punch, and threatens with a perilously close guillotine attempt, but eventually he taps to Chad’s barrage of fists from above.

“The thing about the UCL that’s so marketable is the mystique of the UCL,” said Storm when asked if, in the new climate of acceptance, he’d consider ditching the “underground” aspect. “You always want to keep that mystique,” he said, unwilling to expose his organization to the light of day. “February will be ten years, and there’s nothing that’s really changed about a UCL show — we still do them underground, still word of mouth. I still have the same formula for producing shows, and I’m going to keep it until it gets sanctioned in New York.”

There are usually no doctors or EMTs at Storm’s shows, nor is there pre-fight medical screening. You just show up and fight. Once, an ambulance had to cart away someone who broke their leg, but other than that, the barebones “what you see is what you get” motif has worked like a charm. With no other options for New York-based aspiring fighters to compete locally, the UCL has long been the only MMA game in town.

So what will happen when New York finally starts sanctioning the sport? Will Storm head down to the athletic commission’s office and apply for a promoter’s license, and go legit once and for all? Said Storm without hesitation: “Absolutely.”

Until then, Storm and his UCL will keep keeping on, the lone MMA competition outlet in an area that’s been barren for almost a decade.